Fiennes shines in David Hare’s play about a strong man

★★★

George Bernard Shaw said in his play Man And Superman: ‘The reasonable man adapts himself to the world: the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man.’

In Robert Moses, we have the quintessential ‘unreasonable man’. David Hare’s Straight Line Crazy begins in the 1920s when we meet Moses, an authoritarian figure with a vision of how New York State should develop. And, as he said himself, ‘when you operate in an overbuilt metropolis, you have to hack your way with a meat axe.’ Hack he did, running his straight roads through whatever got in the way.

The play is divided into two parts. In the first, we see the appeal of the strong man. He won’t compromise. He gets things done. He is non-partisan, he uses the law. We admire the way he won’t kowtow to politicians or rich elites. Almost by the sheer driving force of his personality, he gets his roads built: long straight roads to carry working class people (what we in the UK call the middle class), newly liberated by cars, to the countryside. He builds parks and pools and beaches for them to enjoy in their newfound leisure time. In many ways, he’s a hero.

In the second act, at the end of his career, we are presented with the case against his single-minded, big project approach to planning.

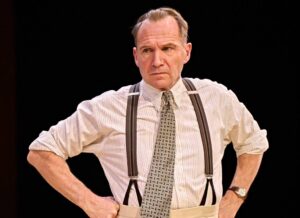

Ralph Fiennes is a perfect choice as the bombastic, heartless Moses. It is a privilege to watch him perform, as he strides across the floor and often planting himself downstage, isolated from the rest of the cast, eyes staring, speaking in that slightly English way that many American patricians had last century, in his case, stemming from his time at Oxford University. However, he is a one-dimensional character. We never really understand what makes him tick, he never expresses any doubts, any warmth or indeed any feelings.

In some ways, Straight Line Crazy is a history of the twentieth century. The love affair with strong men: the Picasso type of artist or the Mussolini style of politician (who supposedly ‘made the trains run on time’), followed by a reaction in favour of co-operation and collaboration. More recently, there’s been a return of interest in so-called strong leaders who get things done, so the play is timely.

If you’re unfamiliar with New York State, you may find it hard to follow what’s going on. In the first act, Robert Moses, a public official who dominated urban planning from the 1920s to the sixties, is pursuing his first great project: to open up the peninsula of Long Island that juts out to the east of New York City and houses Brooklyn and Queens at its beginning and the Hamptons at the other end- home to some of the richest people in America. He wanted to create not only roads but a public beach.

In the second act, he meets his nemesis when, at the end of his career, he seeks to extend Fifth Avenue through one of the city’s most beloved areas: Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village.

This first act spends a lot of time establishing Moses’ commanding personality, with some good dialogue but not a lot happening. Some of the best moments come when Moses interacts with Al Smith, the New York State governor from a poor community and a wily politician who smoothed the way for Moses’ early projects. The ever reliable Danny Webb gives Smith a warmth that enables you to see why he was so popular and persuasive.

Like others who know their own mind and are blinkered to other possibilities, Bob Moses can be a monster. From the start, we get hints that there is a dark side to his character. The people around him work for him, not with him. An employee alters a road design on the instruction of Governor Smith. Moses will have none of it. They are not there to have ideas, simply to carry out his vision.

Act Two is the case against Moses. Much more of his unsavoury side is revealed. He doesn’t change, but by the 1950s the world has. People power is growing. Jane Jacobs declares that cities are about people and communities, talks about the tyranny of the motor car, and has a vision of revived (or gentrified, we might say) urban areas. The writing is on the wall for Moses but he still refuses to consult or compromise.

Bob Crowley’s thrusting set

It looks like David Hare is setting up a battle between Moses and Jacobs, but a clash between two strong leaders would have been counter to the theme of act two. So, although we meet Jacobs, acted with authority and humour by Helen Schlesinger, the play becomes a conflict between Moses and the people (significantly they’re represented by women), a battle between two ages. Speaking for the community is Shirley Hayes, forcefully played by Alana Maria.

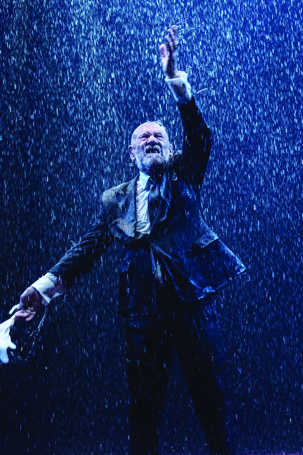

So the rise and fall of Moses is interesting but the fundamental problem with the play is that Moses doesn’t change, except to get older. It is fascinating to see Ralph Fiennes change physically from the upright, vigorous young man to the slightly stooped and more ponderous old man. There is none of the guilt and fear that adds depth to the single-mindedness of Solness, the character Mr Fiennes played in Ibsen’s The Master Builder at the Old Vic in 2016 in an adaptation by David Hare.

There are similarities between the two plays but I’m afraid any comparison would be to the detriment of Straight Line Crazy. Unlike Solness, Moses’ downfall doesn’t come from fear or love or other ‘weakness’, but from a much more mundane cause: changing times and his refusal to change. However, by then, he had achieved so much of his vision, his place in history was assured, so it’s hard to have much sympathy.

The play leaves us pondering about strong leadership and people power, asking ourselves which in the end was more beneficial and which more damaging to the city.

Bob Crowley’s set underlines the debate by using a flat runway that goes from the back of the stage and thrusts out into the audience, like one of Moses’ straight roads. Whenever we meet the protesting community, a wall is flown in that symbolically cuts right through the middle of it, at the same time creating a less thrilling but more intimate space.

Siobhan Cullen and Samuel Barnett play Moses’ two assistants, the former extrovert and good humoured, the other more shy and self deprecating, but both, in their defence of him, giving us an insight into why charismatic leaders attract a following. The younger and less compliant generation is represented in the second act by a new employee, played with passion by Alisha Bailey.

Nicholas Hytner directs proceedings, as he seems to do most productions at The Bridge (we can look forward to him directing The Southbury Child in the summer, and John Gabriel Borkman in the autumn). It’s not only his choice of plays that make him missed at the National Theatre where he was once Artistic Director. His direction is unobtrusive and fuss-free: he puts the script and the actors centre stage. Not for him, distracting gimmicks or clutter; and he has the confidence of a modern strong man who doesn’t need the production to be about him.

Straight Line Crazy performs at The Bridge Theatre until 18 June 2022

Click here to watch this review on our YouTube channel One Minute Theatre Reviews

Click here to read our review of Ralph Fiennes in David Hare’s Beat The Devil