Powerful play by Stephen Beresford about tradition versus populism

★★★★

What timing! The Prime Minister’s ethics advisor resigns and here’s a new play about sticking to your principles. A child has died, a child with the surname Southbury. The mother wants the church to be festooned with Disney balloons; the vicar says this is inappropriate for a church service. It becomes an unlikely cause célèbre and a test of wills that involves the whole community. What follows is an interesting, funny, emotional play about a battle between tradition and modernity.

The stage is a place for conversation. Creators of TV and cinema feel the need to keep us interested by constantly adding action or changing shots or putting on loud music. In a theatre play, the main currency is talk. So Stephen Beresford‘s The Southbury Child has lots of conversation exploring conflicts within today’s society, and, of course, conflict is the basis of drama. Physical acts whether violent or loving have all the more power for being rare.

The play looks at the importance of the past versus the need for change, principles versus populism, minority religion versus a secular society, a patrician elite versus the masses. Such rich content. The obvious comparisons are with Ibsen’s Enemy of the People and Chekhov‘s.. well, anything by Chekhov. I was also reminded of those drawing room plays of the mid 20th century that explored matters of morality, like T S Eliot’s The Cocktail Party or JB Priestley’s An Inspector Calls. In some ways, the dialogue could come from one of those plays. There’s an old fashioned feel to the way that the characters don’t mumble or pause or talk over one another, but it still sizzles. And there is a 21st century feel about the casual swearing and the popular references to Waitrose and Kerplunk.

The specific argument is over what a funeral is for. The vicar David Highland takes the high ground and says he won’t give the mother what she wants but what she needs. I’ve been to plenty of secular funeral services- I’m sure you have- where we’ve celebrated with lighthearted fun a life that has now ended, but, for those of faith, death is not an end but a beginning, and the funeral service offers hope of resurrection as well as a tried and tested way of dealing with grief. His decision throws up far more moral questions.

The vicar himself is far from moral. He’s had an affair, he drinks too much, he’s been in a drunken car crash. So is he a hypocrite? ‘You’re not exactly the poster boy for unshakable principles,’ says his curate. But do we expect too much of our leaders? After all, they’re only human, and isn’t it supposed to be what they represent that we respect, be it a spiritual post or a political position of power? Should we take their lead, even if we disagree with it, or should leaders follow the people?

There’s a lot of emotional conflict going on then, but the dialogue is full of humour. One character says, ‘These days you’re expected to be happy, like you’re expected to be hydrated’ or something like that. David imay be flawed but he seems kind, and well-meaning (which does make his stand against the balloon seem odd).

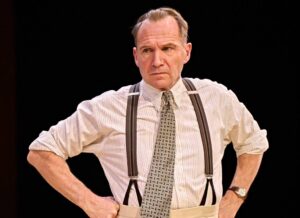

Alex Jennings gives a towering performance as the vicar. He employs a slightly higher voice than his usual rich voice which means he almost slips into an almost Alan Bennett impression, which is just right for some deliciously waspish sarcasm, like imagining heaven would have a branch of Waitrose. (He did play Alan Bennett in The Lady In The Van.) It’s not exaggerated so there is still warmth and authority in his impeccable middle-class speech.

His is the only character given real depth. The others seem to be there to expose or test him. Nevertheless, the sketched outlines of these characters are clever enough to suggest that they have depth. His daughters are both following in his footsteps, in a way. Susannah is a teacher, and his verger, but not fitting well in the world. Her awkward but efficient character is played by Jo Herbert.

The other, Naomi, is an adopted black girl (providing an opportunity to criticise patronising white people). She’s become an actor and, by the way, much is made in the play of the way church services are like shows and priests like actors. David says that the annual blessing of the river is ‘the biggest house I play to’. Racheal Ofori gives a strong performance as the rebellious and somewhat wild young woman.

David’s wife Mary buttons up her feelings and finds it hard to cope with today’s touchy-feely world until it all comes spilling out in one tremendous moment. I did enjoy the way Phoebe Nicholls was able to hunch her body into a shy stiffness.

Craig, the new curate and the candidate for succeeding David, is played by Jack Greenlees. He may be holier than thou or indeed holier than David, but he is a gay man who is required by the church to deny his partner in order to pursue his vocation. Yet another cause and conflict thrown into the mix. As well as the interesting conversations- well, you might call them duels- with David, the other characters also have moments when they bounce off each other. There’s a lot going on.

One character David doesn’t spend much time with is the girl’s mother Tina, played by Sarah Twomey. She is the spark that started the fire but, to give more time to her grief would probably have unbalanced this largely sympathetic look at the way the vicar’s life spirals out of control.

The key opposition from the dead child’s family comes not from Tina but from the child’s young uncle Lee, played with a snarl by Josh Finan. I found myself shuddering every time he was on stage. Lee’s a nasty piece of work without any obvious redeeming feature, yet David as a Christian will not reject him. Lee returns again and again to challenge and needle the vicar.

The play takes place entirely in one room, maybe a drawing room. I don’t know much about the Church of England, however I do know that vicars are not well paid but they are often given a big house to live in. So there’s an appropriately shabby middle-class feel about Mark Thompson‘s set. There’s always a potential problem at Chichester, or any theatre using a thrust stage with an audience on three sides, iun that you can’t have much in the way of scenery. So, apart from a window and a few other pieces at the back, Mark Thompson‘s inspired main features are an image of the church at the back that towers over proceedings and a long wooden table that comes out towards the audience. Around it are 14 odd chairs, symbolic of the broad church perhaps.

Not that people sit down very often. This is a production showing the firm hand of director Nicholas Hytner in which people stand a lot, because that’s more aggressive than sitting, and stride around creating distance or nearness, as the conversation ebbs and flows.

You may find it hard to believe such a conflict could arise from something so trivial seeming, even though the play is apparently inspired by a real incident, but the beginning is nowhere near as contrived as the ending. Be that as it may, the grief at the loss of a child finally comes to the centre stage. And the final scene confirms that this is a play about loss of many kinds, both personal for many of the characters and for society, in terms of our traditions and heritage.

The Southbury Child performed at Chichester Festival Theatre until 25 June 2022 (tickets cft.org.uk) then at the Bridge Theatre from 1 July – 27 August London SE1 (bridgetheatre.co.uk)